ERAA 2025 Edition

Key takeaways

ERAA 2025 shows that significant volumes of fossil‑fuelled capacity are likely to become economically non‑viable over the coming decade, as revenues in the energy‑only market are insufficient to sustain parts of the existing fleet. Action is therefore needed to maintain the security of electricity supply in Europe

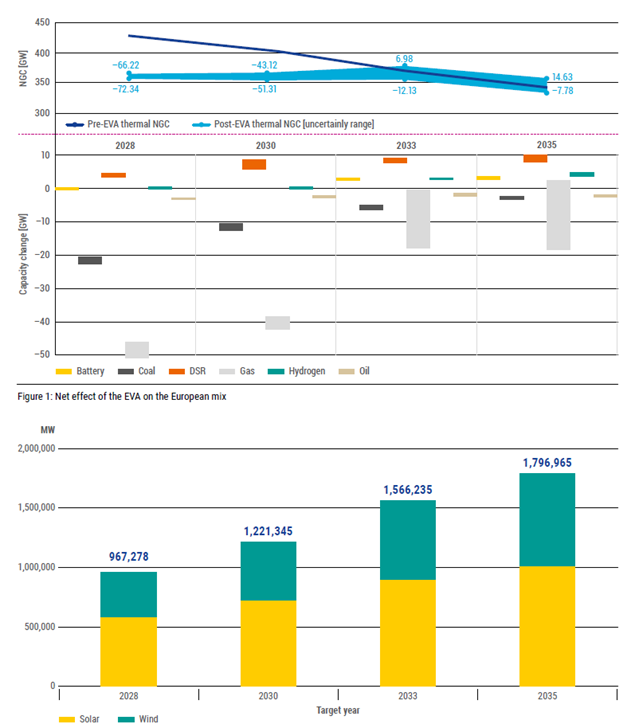

In the short- and midterm (2028 and 2030), significant capacities are at risk of being decommissioned, with a moderate uncertainty range (around 6–8 GW). In the longer term (2033 and 2035), decommissioning risks remain for the assumed thermal generation fleet, and only in 2035 does the model indicate some potential expansion of gas‑fuelled and emerging hydrogen‑fuelled generation. However, this expansion is uncertain and depends on the investment strategies adopted by investors, as well as on favourable conditions outside the ERAA scope, such as supply chain constraints, electricity network development, and primary energy and hydrogen availability.

The development of the power system must therefore be closely monitored to confirm that investment needs are being realised. ERAA 2025 demonstrates that different investment strategies, particularly different approaches to investor risk aversion, have a major impact on resource adequacy. Relevant authorities should reflect on possible mitigation actions to secure European adequacy. While the assessment assumes that many investments could be driven by scarcity prices in hours of high demand or tight supply, the report explicitly recognises that rational, risk‑averse investors may discount or disregard rare, extremely high price spikes as a reliable revenue source, especially in the absence of long‑term contracts or stable support schemes.

Decommissioning of existing power plants should likewise be monitored to ensure it does not exceed anticipated levels. Renewable generation capacity is expected to expand substantially based on national policy targets and TSO estimates. Yet, because of intermittency, this expansion will not be sufficient on its own to fully compensate for the decline in dispatchable thermal capacity and the substantial increase in electrification by 2035.

ERAA 2025 modelling suggests that different investor risk aversion assumptions can lead to a wide range of future capacity outcomes; by 2035, the power supply fleet may vary by up to 21 GW purely due to differences in investment strategies. Although market opportunities are identified for storage, demand‑side response (DSR) and, in some zones, new flexible gas and hydrogen‑fuelled units, overall viable capacity remains strained in the central reference scenario. In addition, the long‑term equilibrium tendency of the economic model to rely on rare scarcity hours is explicitly curtailed by a revenue cap, reflecting that revenues from extreme price spikes are too uncertain to underpin real‑world investment decisions. Relying solely on such scarcity‑driven new entry would risk underestimating adequacy challenges.

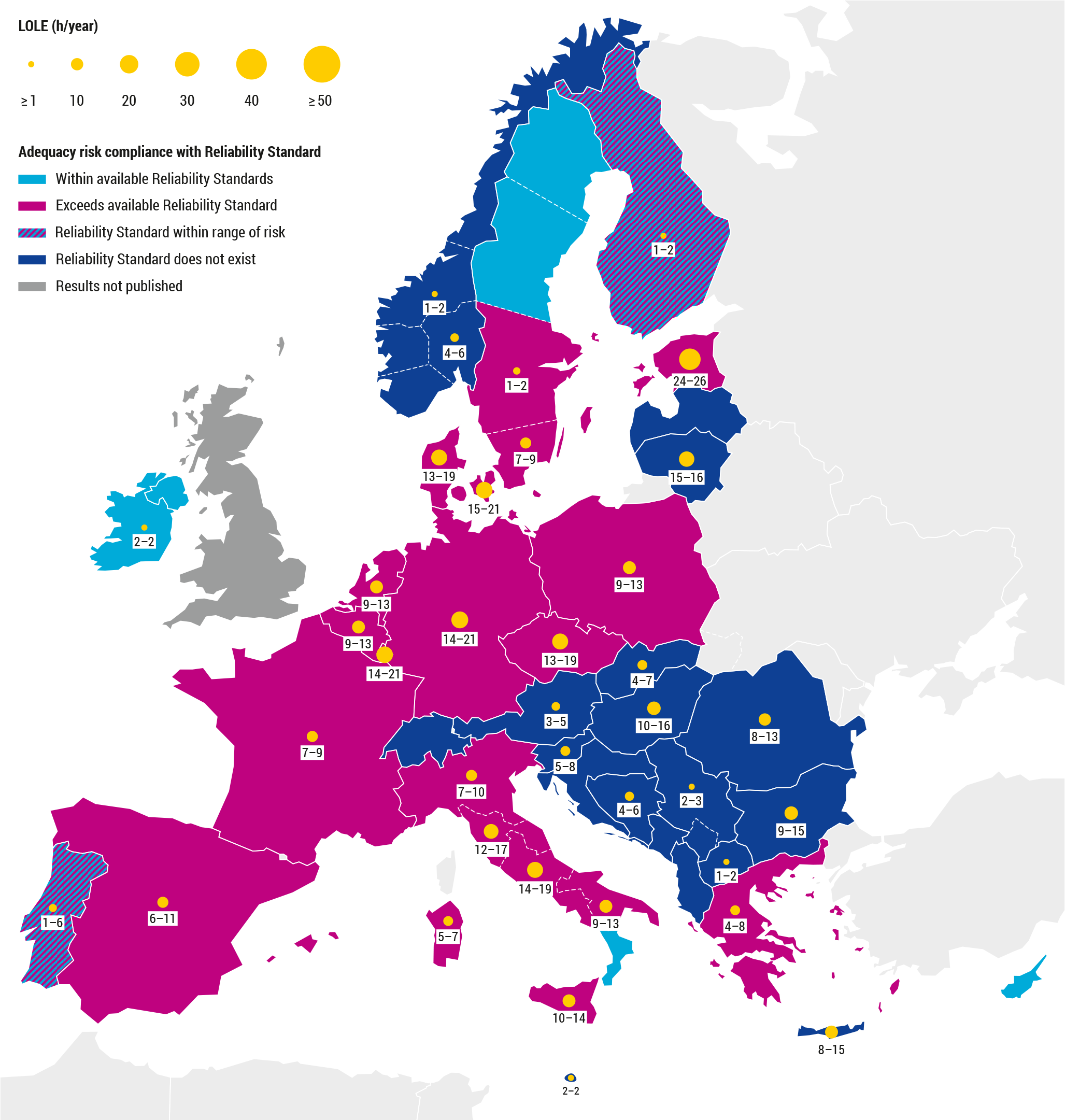

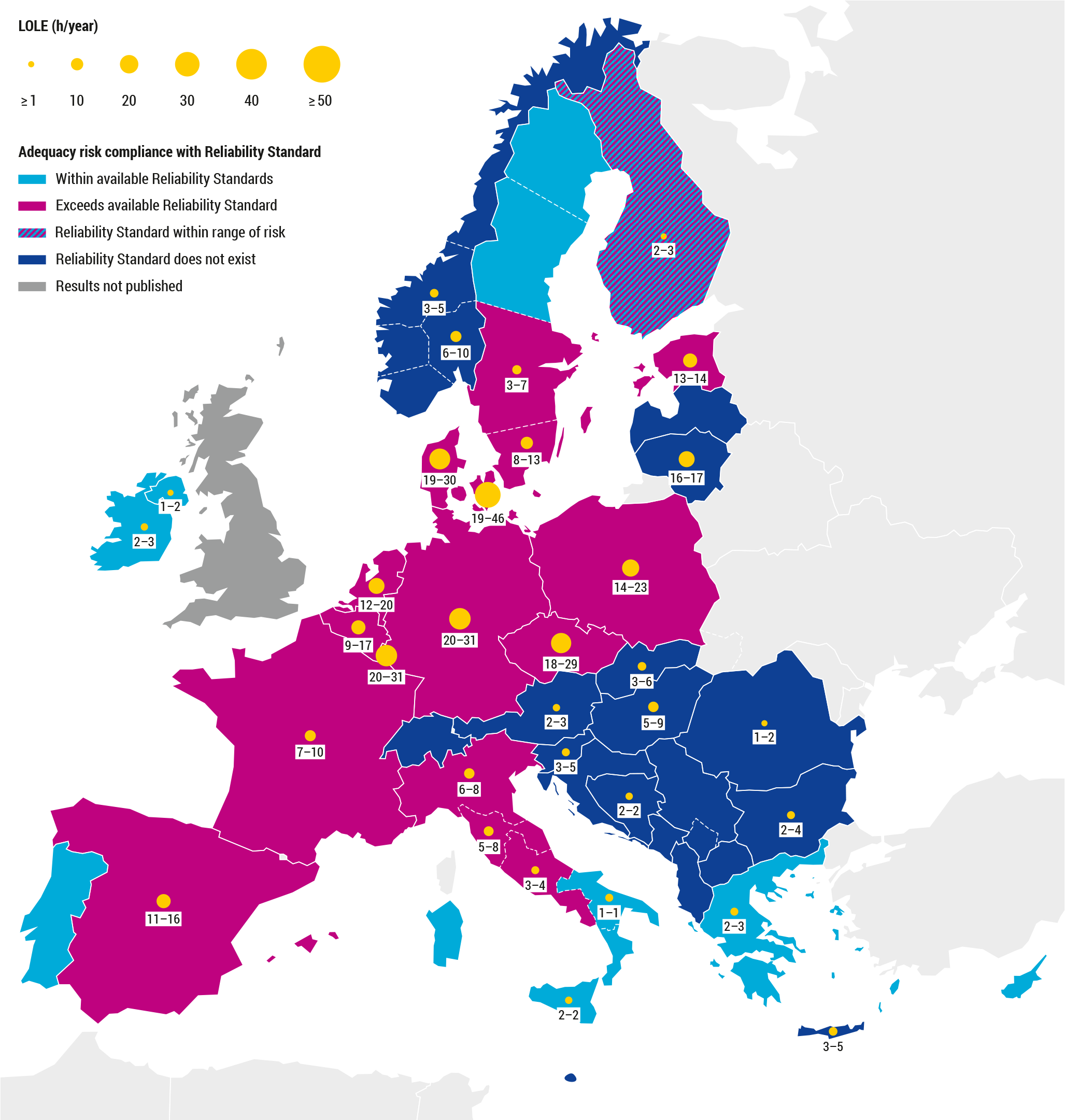

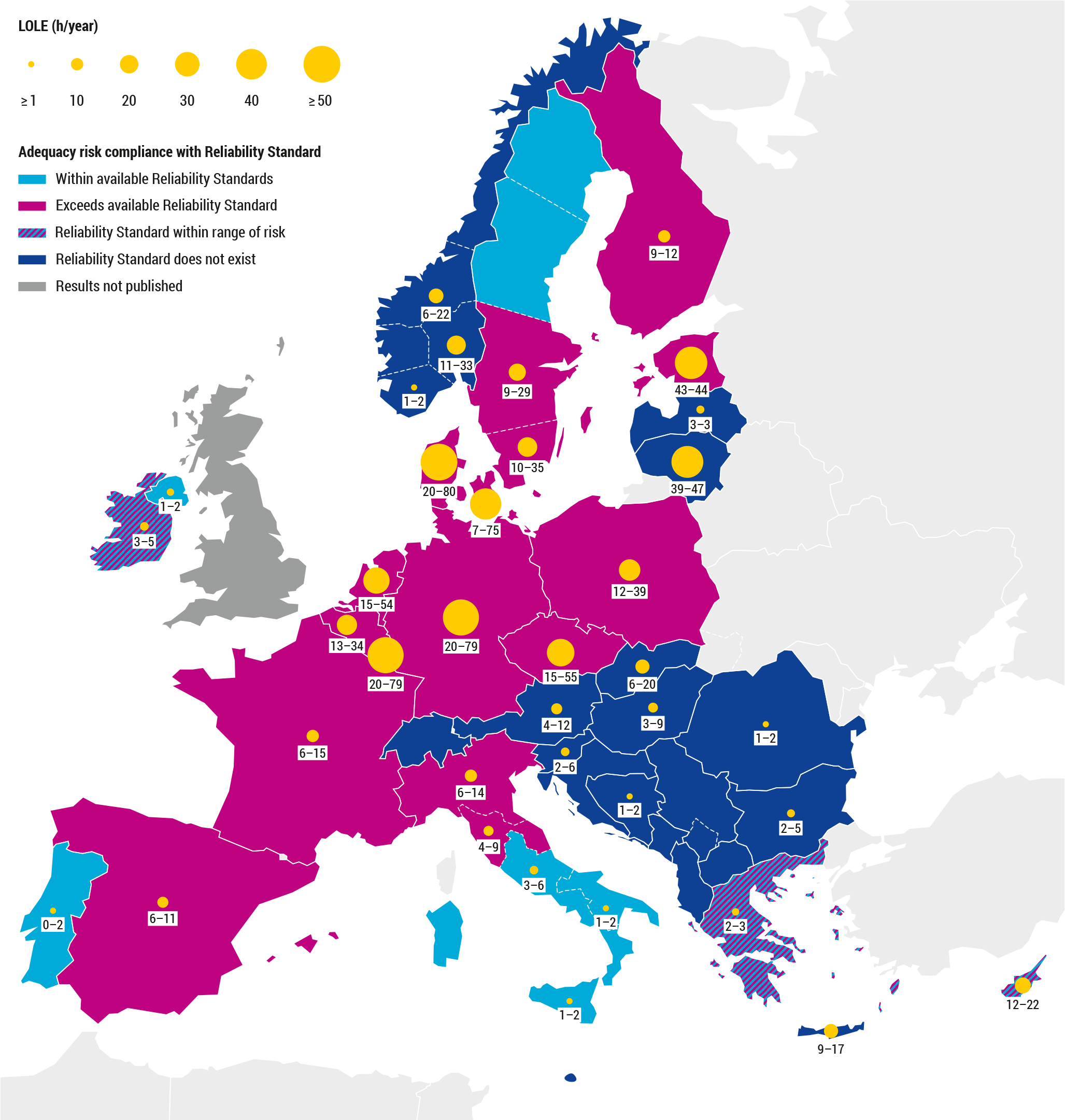

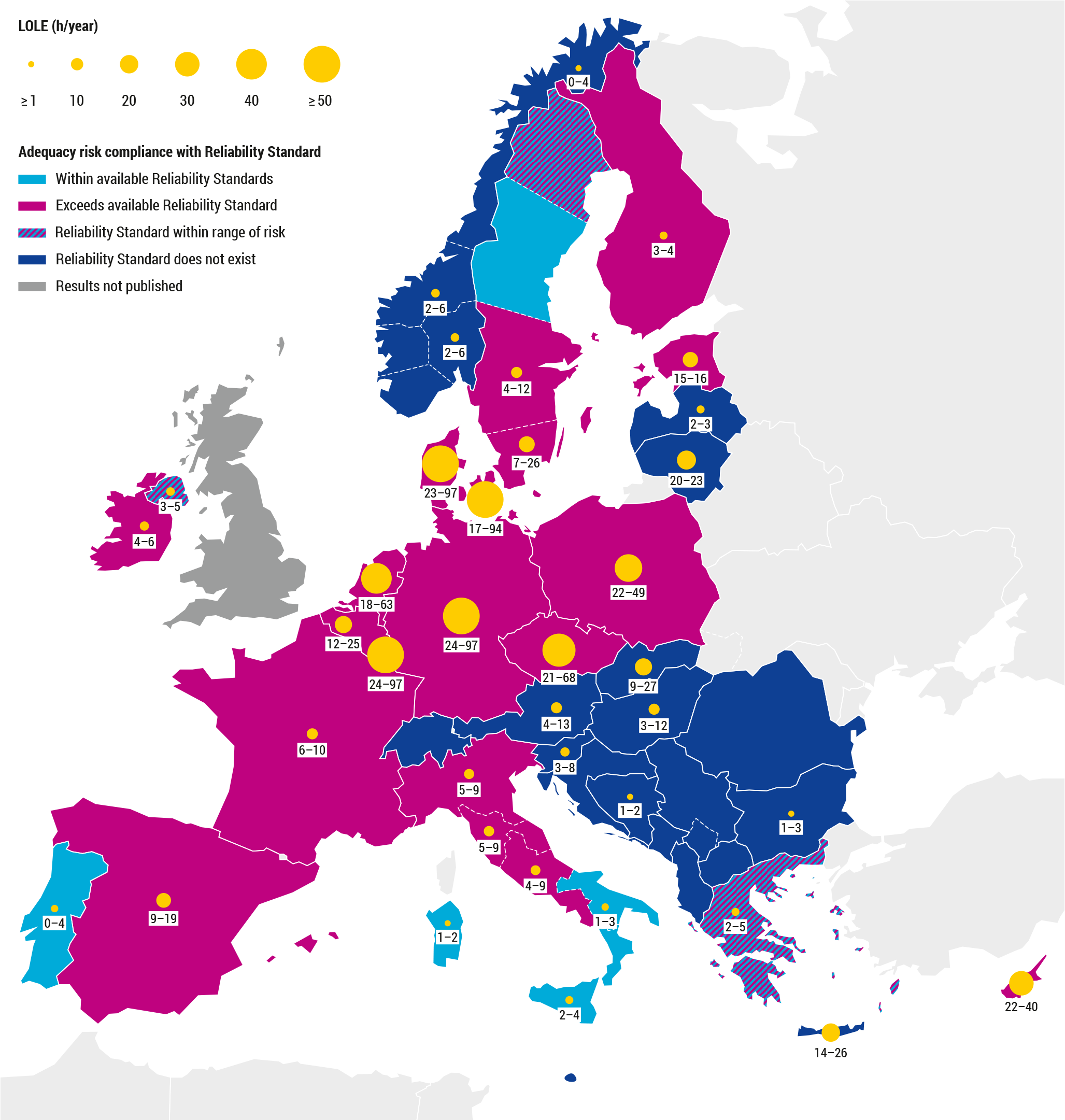

Notable adequacy risks exist across Europe. Available national reliability standards are exceeded in many study zones, and only occasionally are adequacy risks below (i.e. compliant with) these standards. Risks generally increase the further into the future the assessment looks, although they tend to be lower in parts of the Balkans and Scandinavia. Existing non‑market adequacy resources (such as contracted strategic reserves) are already included; where notable adequacy risks remain, this indicates the need for additional resources or measures.

Targeted interventions and long‑term market mechanisms are therefore essential to avoid further risks. Supporting mechanisms and capacity markets should be accelerated where necessary to enable the energy transition while maintaining system security until effective incentives and/or targeted interventions are fully in place. To ensure electricity security and achieve climate objectives, Europe must speed up the deployment of flexibility solutions and infrastructure, including cross‑border transmission to move renewable electricity where it is most needed, as well as storage, DSR and other sources of flexibility, while always safeguarding security of supply.

The ERAA should be considered in conjunction with national resource adequacy assessments (NRAAs) to inform EU Member States and National Regulatory Authorities about the level of security of supply and to support decisions on different market design options, including capacity mechanisms. NRAAs provide a complementary, more detailed picture of national specificities and local sensitivities, thereby enriching the pan‑European overview of capacity concerns that ERAA provides. The two sets of assessments are intended to be used together.

Lastly, ENTSO‑E stresses that the primary purpose of ERAA goes far beyond serving as a mere tool for centralised decisions on CMs. ERAA supports policymakers in identifying adequacy concerns and building mid‑ and long‑term strategies, using pioneering methodologies and tools to analyse future adequacy with an unmatched combination of scope and detail. In parallel with the Electricity Market Design Reform and the new Clean Industrial Deal State Aid Framework, ENTSO‑E has proposed amendments to the ERAA methodology to ACER, aiming to improve robustness, streamline the framework, enhance complementarity with NRAAs, and provide additional parameters useful for simplified CM approval. Methodological innovation, pilot projects, stakeholder consultation and careful refinement of the ERAA scope will continue to strengthen its usefulness and empower policymakers to make well‑informed decisions that support both national and EU objectives.

Main findings

Economic Viability Assessment Findings

ERAA 2025’s Economic Viability Assessment (EVA) finds that substantial volumes of fossil‑fuelled generation across Europe are at risk of becoming economically unviable in the energy‑only market, even before reaching technical end of life.

Using a cost‑minimising, system‑wide planning model, the EVA shows that, once capacities already backed by capacity mechanisms or policy support are excluded, large amounts of gas, coal, lignite and oil capacity are likely to decommission between 2028 and 2035, with only limited life extensions and targeted new entry. While there is some market‑driven scope for additional DSR, storage and, from 2033–2035 onward, new gas‑fired OCGT/CCGT and first hydrogen‑fuelled CCGT units in certain zones, these additions do not fully offset thermal exits, leaving overall market‑viable capacity “strained” in the central scenario. A key insight is that investor risk aversion materially changes outcomes: by 2035, the total fleet can differ by up to 21 GW depending on whether investors only apply higher hurdle rates or also discount revenues from very rare, extreme price spikes through a revenue cap. This underscores that relying on scarcity prices alone, especially those from exceptional events, to trigger sufficient investment is unrealistic, and that without additional policy support or long‑term mechanisms, the economic drivers identified by the EVA would lead to a net loss of firm capacity and higher adequacy risks.

Adequacy Findings

The results of the EVA naturally have a significant impact on the adequacy assessment. Adequacy risks appear in several European countries and margins are tight, with risks generally increasing the further the assessment looks into the future. The uncertainty range around these risks reflects the impact of different investment strategies and investor risk‑aversion assumptions on the amount of market‑viable capacity.

The LOLE values are represented by circles, with a larger radius indicating a larger LOLE value. A study zone’s LOLE is calculated by averaging the Loss of Load Duration (LLD), i.e. hours with unserved energy, resulting from all simulated Monte Carlo years using the reference tool.

More detailed results, including Expected Energy Not Served (EENS) per region, can be found in Annex 3. For the methodology and probabilistic indicators, please see Annex 2. Moreover, there are cases where the results depend on the specific characteristics of each country or study zone. Annex 6 provides country-specific comments that enable more detailed conclusions.

Further remarks on result interpretation

Being an inherently complex study, ERAA 2025 is characterised by a high degree of uncertainty and significant computational constraints. Consequently, the modelling decisions and assumptions, as well as the probabilistic nature of the assessment, must be carefully considered when interpreting the results.

ERAA 2025 introduces impactful methodological enhancements compared to previous editions, notably in the modelling of investor risk aversion in the EVA and in the selection of representative weather scenarios. At the same time, assumptions for a given target year can change rapidly from one edition to the next due to the accelerating energy transition and the continuous update of policy and system data (e.g. revised NECPs). Comparisons between ERAA 2025 and earlier editions should therefore be made with caution, taking into account both input data updates and scenario changes, as well as methodological improvements that can materially affect adequacy outcomes.

ENTSO-E

ENTSO-E